Relics of warring daimyos

Those who have been following the FX miniseries, “Shogun,” adapted from the bestselling James Clavel’s novel of the same title, will find themselves wandering through the corridors of The MET to see mementoes of the daimyos in “Samurai Splendor: Sword Fittings from Edo Japan,” on display in Gallery 380.

New York’s The Met is home to the most extensive collection of Japanese artifacts from the shogunate period outside of Japan itself.

Cradled in its exhibits are a wealth of objects from Ashikaga to the Tokugawa eras, including intricately designed tsuba or sword guards, the awe-inspiring o-yoroi, a suit of armor, once worn by a Ashikaga Takauji himself!

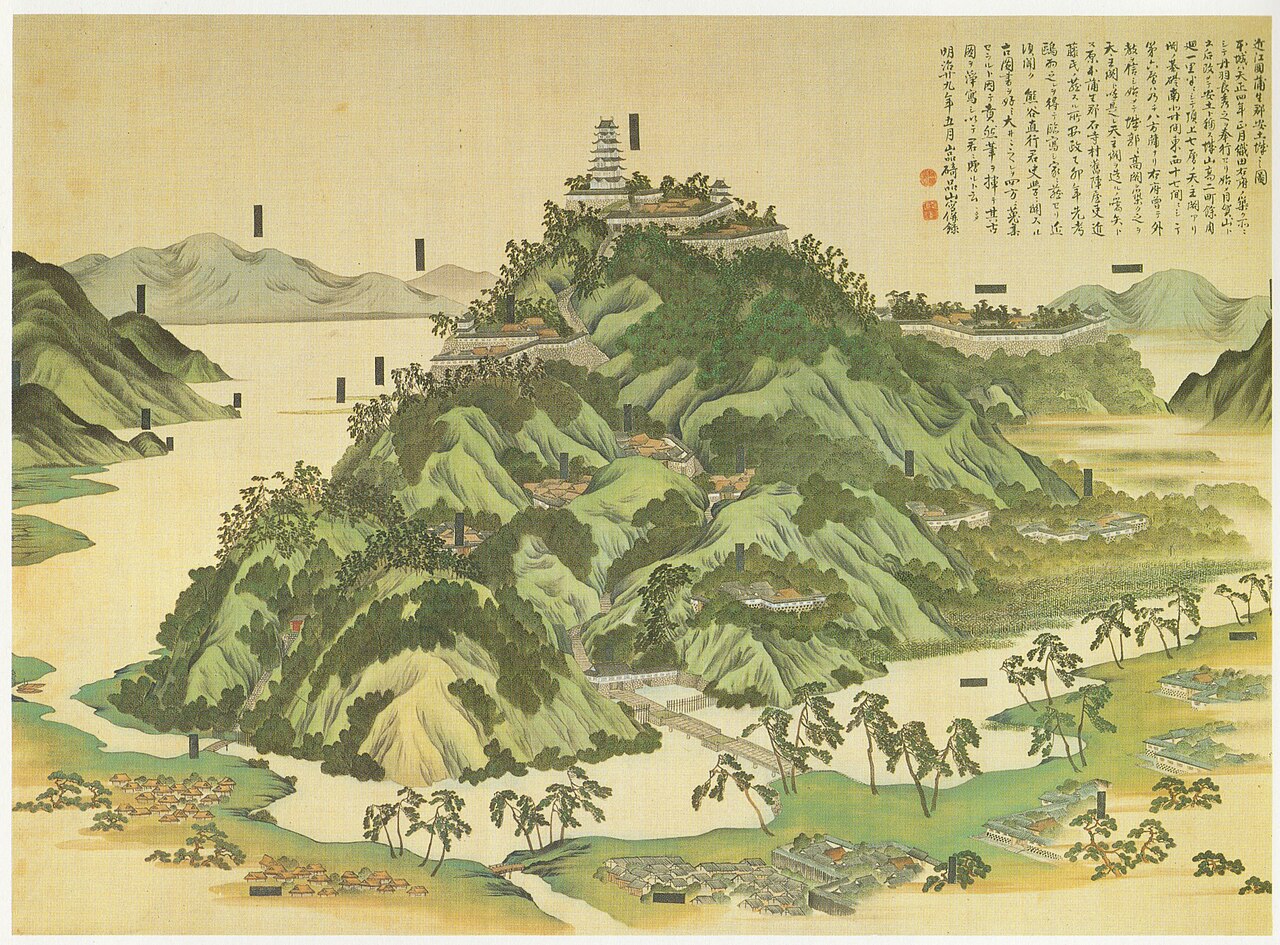

The rise of the warlords came at the factious period of Japanese history when feudal lords from different ruling families across Japan clashed for supremacy. In a protracted and bloody campaign to unite the nation, three daimyos stood out for their ambition, tenacity, and military prowess: Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and Tokugawa Ieyasu.

Initially, his clan thought of Nobunaga as an unworthy successor of his father to take over the clan’s mantle of leadership, but he proved them wrong. A cunning military strategist, Nobunaga thwarted threats from his own family, and those from neighboring provinces. It was a time when betrayal and bloodshed were far too common.

A Portuguese ship en route to China was shipwrecked on the Japanese coast, and aboard were arquebuses that Nobunaga recognized were a game-changer. Armed with this revolutionary weapon, he and his men clobbered the enemies and helped him consolidate his power as he expanded eastwards.

Even with a string of victories, Oda Nobunaga wasn’t entirely secure. While Hideyoshi led a campaign in the east on his behalf with some of Obunaga’s most able warriors, Nobunaga was left with a treacherous ronin. Bereft of security from within, Nobunaga’s severely undermanned defense against a siege ultimately led to his suicide.

Even with a string of victories, Oda Nobunaga wasn’t entirely secure. While Hideyoshi led a campaign in the east on his behalf with some of Obunaga’s most able warriors, Nobunaga was left with a treacherous ronin. Bereft of security from within, Nobunaga’s severely undermanned defense against a siege ultimately led to his suicide.

In the aftermath, Toyotomi Hideyoshi rose to fill Nobunaga’s shoes. Unlike Nobunaga, Hideyoshi’s ambitions included conquering China; however, geographical realities had siphoned off an enormous strain of resources and labor of the allied western daimyos.

Later, pondering on his mortality, Hideyoshi chose to leave the care of his successor to a council of advisors. Meanwhile, his ally, Tokugawa Iieyasu, subsequently seized power and Hideyoshi’s heir took his own life.

Having consolidated power, Ieyasu ushered Japan in a period of peace that lasted through two centuries until the American naval commander Matthew Perry forced Japan to open its ports in the 1850s.

Back to The Met, it’s fortuitous that the venerable institution holds this rare exhibit of mementoes from this remarkable period of Japanese history. A visit by any ardent student of Japanese culture will be rewarded with an enriching experience of a rare interface with uniquely designed yet powerful pieces of artifacts that were once worn or used by formidable figures of history.